By Pauline Barmby | February 11th, 2020

The universe that astrophysicists study is really big, but the social universe we inhabit is pretty small. When we meet one of our colleagues for the first time, it usually doesn’t take very long to figure out that we have friends or co-workers or projects in common. For the five of us, all professors in the Department of Physics & Astronomy at Western University in London, Canada, the Spitzer Space Telescope is our common link. It sent us on separate journeys that landed where none of us expected, but all are glad to be. We’re the largest group of Spitzer alumni in Canada, although only one of us is Canadian. We study vastly different areas in astronomy but all work together. And we’re all proud of our Spitzer history and grateful for the experiences it gave us.

(Left to right) Els Peeters, Jan Cami, Pauline Barmby, Sarah Gallagher, Stan Metchev

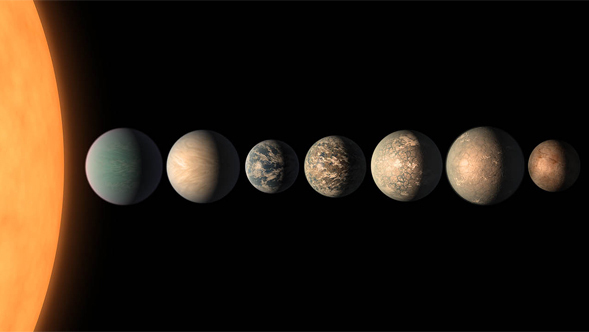

Stanimir (Stan) Metchev is the most recent addition to Spitzer North, having joined Western in 2013 from Stony Brook University; before that he was a Spitzer Fellow at UCLA. He is a Canada Research Chair in Extrasolar Planets and uses Spitzer to study weather on brown dwarfs and to detect any planets that may transit in front of brown dwarfs. His research group received the largest-ever allocation of Spitzer observing time to a Canadian group for their project to monitor “Ultra-cool dwarfs viewed equator-on: surveying the best host stars for biosignature detection in transiting planets.” Their discoveries with Spitzer include the ubiquity of weather phenomena on brown dwarfs and a candidate temperate exo-Earth with the coolest known (L dwarf!) host star.

“Exoplanets and brown dwarfs were merely hypothetical objects awaiting discovery in the far-distant future when Spitzer was conceived. Yet, Spitzer has left a most lasting legacy in these fields, and they have delivered some of Spitzer’s highest-visibility results, most of which from the Spitzer Warm Mission. Thank you, Pauline Barmby, for your exquisite work on the IRAC camera!”

Sarah Gallagher was also a Spitzer Fellow at UCLA, from where she came to Western in 2008. Her Ph.D. research on quasars and compact groups of galaxies used two more of NASA’s Great Observatories (Hubble and Chandra), so it’s no surprise that space astronomy has been a focus of her career. She now splits her time between Western and the Canadian Space Agency, where she is the Science Advisor to the President.

“Between my first and second postdocs, I moved from the East Coast to the West Coast of the US and went down 5 orders of magnitude in frequency from X-rays to infrared light. Incorporating Spitzer data into my research gave me new insights into the energetic winds from supermassive black holes and turned me into a true multiwavelength observer.”

Els Peeters and Jan Cami joined the Spitzer family as postdocs at NASA Ames in Mountain View. Although the two Belgians lived and worked in California for only a few years before coming to Canada in 2007, we still haven’t been able to convince them the temperature difference isn’t *that* bad. Els’s research on large carbonaceous molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons has used the Infrared Space Observatory (ISO), Spitzer, and the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), and she is looking forward to using the James Webb Space Telescope as co-PI of the Early Release Science project Radiative Feedback from Massive Stars.

“Spitzer gave us the ability to correlate the fingerprints of large molecules with distinct changes in conditions across the region in which they reside. This has led to the realization that the population of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in their host environment is not static but rather endures significant processing.”

Jan’s big moment with Spitzer was the discovery of buckyballs in space in 2010. This started a new research field and led to many follow-up projects that have seen him travel to telescopes and give public talks around the world. He says, “When we moved to California, I was still working on my ISO data, and thought Spitzer wouldn’t add that many important discoveries to ISO’s infrared legacy. Boy, did I prove myself wrong! Spitzer’s sensitive view on those buckyballs has changed my life!”

As the member of our group who spent the longest time working directly on Spitzer, I got to write this story. I’m Pauline Barmby and I started working with the IRAC instrument team at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in 2001, two years before launch. While on the Spitzer team, I learned about what it takes to get a space mission off the ground, as well as more three-letter acronyms than I ever would have believed existed. I remember the thrill of seeing the first IRAC images and the only-slightly-mad scramble to analyze them and show how well the instrument worked. It was pretty exciting to be at NASA Headquarters for the release of the first Spitzer images! My spouse and I have a “Spitzer baby” -- born in 2004 about a year after launch -- who is now a strapping 15-year old. I left SAO for Western in 2007 but kept involved as a Spitzer user and proposal reviewer right to the last observation cycle.

Spitzer has shaped all of our professional lives even though we all ended up at Western in different ways and for different reasons. It taught us not just about brown dwarfs or buckyballs, but about how a big project comes together out of many small teams. We learned how to train the next generation of astronomers - between us we have supervised the research of nearly 50 students who used Spitzer and brought a new area of expertise to Canadian astronomy. And we were brought together and couldn’t be more pleased to be part of the Spitzer North team.

From Happy Developer to Good Manager: A software programmer learns to manage code and people at the SSC

From Happy Developer to Good Manager: A software programmer learns to manage code and people at the SSC

Being Part of Spitzer is Being Part of History

Being Part of Spitzer is Being Part of History